For decades now, it has been an item of faith that the free market is not only economically advantageous but also politically essential. World trade has been considered an essential guarantor of world peace. The idea that the world will be at peace if nations trade with each other goes back at least to Emile Crucé’s Le nouveau Cynée of 1623, which called for world federalism and peace through free trade. Nearly a century later, the Abbé de Saint-Pierre proposed a ‘European Union’ to facilitate commerce between nations; Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), an avid reader of the Abbé de Saint-Pierre, took over the idea and argued peace and unity in Europe could be achieved precisely because the continent was already united in commerce.

The school of positivism founded by Henri, comte de Saint-Simon (1760-1825), took the argument one step further. He and his disciples wanted to de-politicise governance completely by placing it in the hand of industrialists and engineers. Only when politics was completely absorbed into economics would there be peace. Although Marx and Engels developed their own form of socialism, in opposition to that of the positivists, they also argued vigorously that economics should replace politics and even that free trade would hasten the necessary world revolution by destroying institutions like the family and the national basis of production. World peace would then come about through communism, i.e. through the economy, because the contradictions of capitalism would cause it to disappear, together with the states which sustained it, the state being nothing but an instrument to ensure the economic oppression of one class by another.

So deep was the conviction that war was against economic logic, and that peace would come about through the effacement of states, that when the British Labour politician Sir Norman Angell penned his The Great Illusion in 1909, it became a best-seller and even a sort of cult book. He argued that wars would cease because they made no economic sense. The First World War which broke out shortly afterwards did not cause people to doubt his theory: the Nobel committee awarded him the Peace Prize in 1933, just as the Nazis came to power and the Second World War was starting to brew. After the First World War, the League of Nations was set up to ensure peace but so was the International Labour Organisation which, unlike the League, still exists today. According to the preamble of its Constitution, world peace can exist only if there is social justice. In other words, economics is the key to peace because labour is the basis of the economy. Similarly, at the New York World Fair, which opened in April 1939, a group of businessmen created the ‘World Trade Center’ dedicated to ‘world peace through world trade.’ Just as the First World War did not seem to invalidate this sentiment, nor did the Second: ‘World Peace through World Trade’ was adopted by IBM as its company slogan in 1949.

A year later, in Paris, the disciple of Henri de Saint-Simon, Jean Monnet, concocted his plan to establish a European Coal and Steel Community which would promote peace by amalgamating the coal and steel industries of Europe. Monnet would later epitomise his thought with a pithy slogan printed on the front page of his memoirs: ‘We are not making a coalition of states, we are uniting people.’ The European ‘common market’ became the foundation stone for peace, consolidated, from the Maastricht treaty onwards, by a single currency whose primary goal was said to be the completion of the single market. By trading with each other, by recognising each other’s standards and by using the same currency, Europeans would put aside their historical grievances and live together in post-national harmony.

After the fall of the iron curtain, these beliefs were turbocharged by the new ideology of globalisation. The old relatively informal General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) became the World Trade Organisation in 1995. According to the ideology, cheesily formulated by Thomas Friedman, no two countries which both had McDonalds would go to war. It was on this basis that everything from industrial production, including high-tech, to energy supplies became intensely globalised. Entire swathes of industry and raw materials production were closed down (France does not mine any more metals, for instance, but imports all its metal from abroad) and outsourced to China and elsewhere.

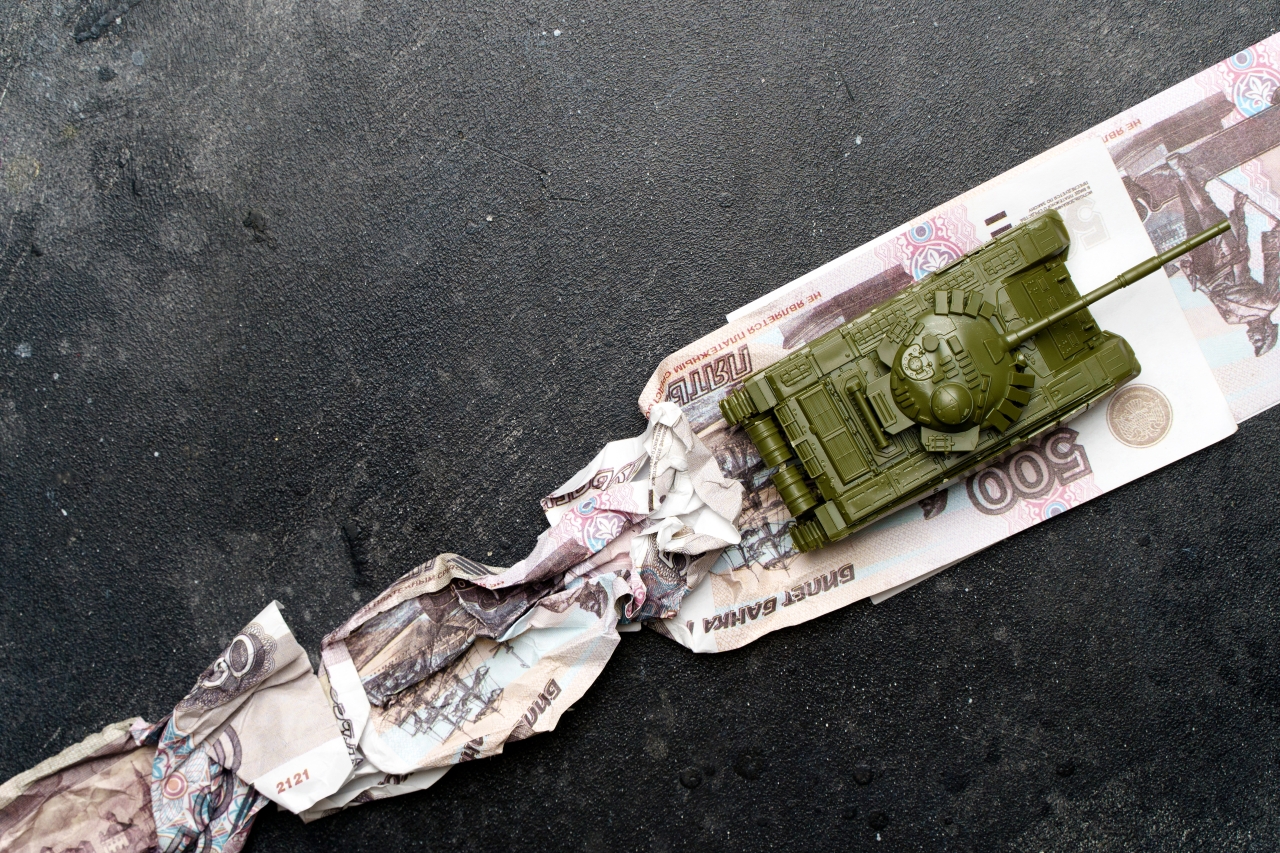

The Ukraine war seems to have driven a coach and horses through this centuries-old belief. By applying massive sanctions, the goal of which is to ‘wage a total economic war against Russia’ and ‘to cause the Russian economy to collapse’ (in the words of the French Finance Minister, Bruno Le Maire in March 2022) the West has tried to turn the world economy from a vector of peace into an instrument of war. Those same Western companies whose presence in Russia was supposed to ensure that Russia would align its foreign policy, and indeed its entire culture, on those of the West, have been forced to close down their operations and return home.

Independently of the question whether the sanctions are working, and whether Europeans will suffer from their effects more than Russians, this is a very arresting development. It appears that the West has abandoned 30 years of globalist ideology to adopt, instead, something resembling Napoleon’s continental blockade (1806-1814) designed to bring Britain to her knees.

But in fact what this apparent volte-face has revealed is the reality beneath the apparent liberalism of the globalist ideology. As we can see from the language of the ‘Great Reset’, globalist ideology is not about increasing freedom but instead about increasing managerial control through top-down policies decided by elites. Every single word which falls from Klaus Schwab’s lips is based on the assumption that human society is dangerously anarchic and that it needs to be centrally managed, at the global level. If globalists are hostile to national sovereignty, it is not because they are in favour of individual freedom against the supposed authoritarianism of states, but instead because sovereignty embodies for them that (collective) freedom and unpredictability which they cannot abide.

The world economy for them is a machine, or a computer which can, and should be, reset at will because its free growth has proved irrational. Globalism is the very opposite of liberalism in the Hayekian sense of a spontaneous order which emerges when individuals make choices about the infinite number of personal situations in which they find themselves; it is, on the contrary, a rationalist and indeed neo-socialist programme for worldwide social and economic control. This is why, among all the state leaders who visit Davos, the one to whom Klaus Schwab is the most obsequious and deferential is none other than the head of the largest Communist state in the history of the world, Xi Jinping. China is the globalists’ model.