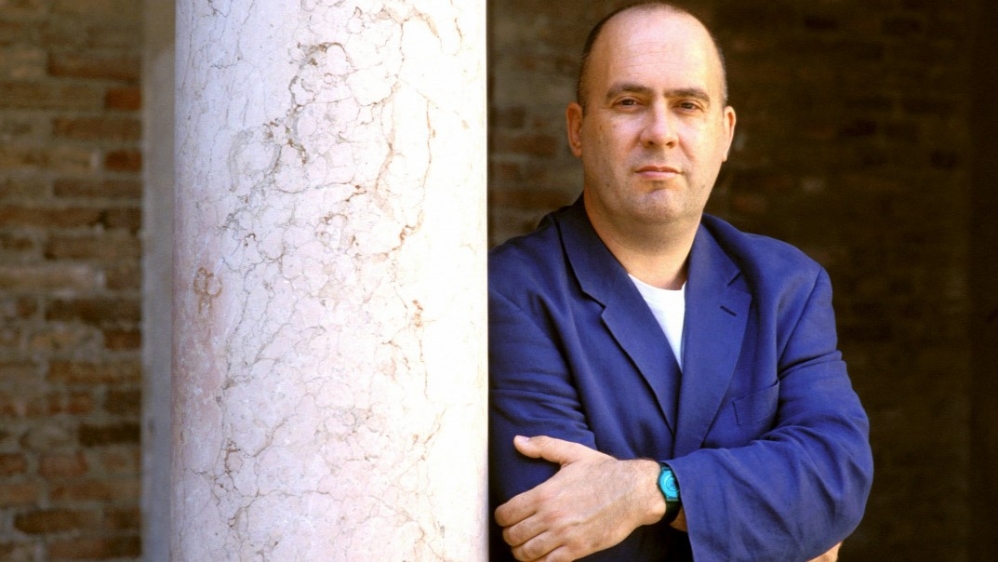

His father had arrived in London with only clothes on his back in 1956 but at the end of his career retired from the BBC Radio's management. Fischer first visited Budapest after his university studies and later spent here years as correspondent reporting on the end of Communism and the regime change in Hungary. This time he moved to Budapest to build up MCC's Center for Literature. We talked about his family, identity, and also his plans in MCC.

You were born and grew up in England as the son of '56er Hungarian refugees. Recently you moved to Budapest to head MCC's literature center. “Moved” or “moved back home”?

Well, both. I’ve always felt at home in Budapest. It’s a great city and the only city where I’m likely to bump into my cousins in the street or in a supermarket. My parents left in ‘56, but everyone else stayed, so I get a lot of free meals. And free advice.

Did you have any picture in your mind about Hungary as a child or made any flying visits behind the Iron Curtain?

My mother only came back after thirty years, my father after thirty-two. I came for the first time, after I graduated, in 1982 when I was twenty-two. Hungary came mostly from books for me, but I also heard about it from my parents and other emigres in London.

Your father built up quite an outstanding media career working for the BBC and Radio Four while after high school you ended up studying languages in Cambridge. This appears to be an integration success story. Was it?

My father had remarkable success in the BBC. If I were to win two Nobel Prizes, I wouldn’t have achieved what he did. He arrived in England with the clothes on his back and fifteen years later he was in charge of the spoken word for BBC Radio.

I didn’t integrate, I was born there. The atmosphere at home, when I was growing up, was: we live in England now. For all sorts of reasons, the door to Hungary was closed. My father wanted me to have nothing to do with Hungary. But then he shouldn’t have named me Tibor.

Did this sort of duality have an influence on the topic choice for debut novel “Under the Frog”? The book tells the story of Hungarian basketball players in the Soviet-occupied Hungary until 1956.

I didn’t write “Under the Frog” as a family history.

Obviously, some of it came from my parents who were both basketball players. My mother, Margit Fekete, was the captain of the National team at a time when they were second only to the Soviet Union. She liked to remind my father about that from time to time.

But I worked in Hungary as a journalist from 1988-90, I was here for the Big Show, and that put me in contact with all sorts of people from the top of society to the bottom, Ministers to rent-boys. Envisioning Hungary in the 1950s wasn’t such a huge leap of imagination then. The bullet holes were still in all the buildings in the centre of Budapest. Nearly everything in “Under the Frog” is true, i.e. the experiences were real, they happened to someone.The thing that pleases me most about that book is that many readers of that generation think I’m a 56er too. I’ve also got an entry in the big history of Hungarian Literature where the late, great Mihály Szegedy-Maszák argues that I’m in fact a Hungarian writer, I’m just pretending not to be one.

So, the question naturally arises: If you’re asked about your identity how do you answer? British of Hungarian descent? British-Hungarian? Neither of those?

It’s a question I’m asked a lot. Do you feel British or Hungarian? I say I feel like me. But I might object to being described as Belgian.

What convinced you to accept this position?

The idea of teaching what I like, as opposed to someone else’s syllabus, is very appealing. Plus, I’ve spent most of my life in London, and I’m now very happy to live somewhere more manageable. You have to organize your social life like a military campaign in London. My nearest friend in London is a forty-minute walk away. Most of them are an hour away. And it rains a lot. Budapest is the perfect size for a city, big enough to have everything, small enough to be enjoyable. I mean you can almost stroll through most of Budapest in little more than an hour.

I’m sure the management will review your request. And how do you like to teach?

Ideally, teaching on a beach in Nice, but failing that, if you have students that are motivated, teaching can be fun. If they’re not motivated, it isn’t.

MCC is home to hundreds of outstanding, talented students who envision their future in multinational companies, law firms to start-ups or in the public administration. How would you convince them that between two internships and a case solving competition they need to dedicate time for literature?

It’s clearly my mission to bring some sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll to the MCC. Companies, governments come and go. Literature remains.

Finally, is there any Hungarian writer or books you especially like?

My favourite Hungarian writer, by far, is Sándor Márai. Why? Because of his character and because of the lack of fuss in his writing. There isn’t one book I’m particularly fond of. I reread the diaries all the time. If I had to champion one Hungarian novel, I’d be tempted to select Móricz’s “Relatives”, which explains Hungary better than any book I know. I was very keen on Gárdonyi’s “Slave of the Huns” (Lathatatlan Ember) when I was a kid.

Cover: AFP.