In May, Wallowa County in northeastern Oregon could become the twelfth to vote in favor of moving state lines. In the second phase, Greater Idaho would be enlarged further to include southwestern Oregon’s GOP-voting coastal counties, as well as a chunk of northern California. The pro-Greater Idaho camp acknowledge that the chances of their unprecedented fight are “perhaps less than 50/50 in this moment in history” because approval would be required from both the states involved and the U.S. Congress. However, they seem determined to persuade Portland to let the eastern counties go through petitions and campaigning.

It comes as many Democrat-controlled cities across the country are steadily descending into the abyss of violent crime. In 2020, far-left protesters in Portland barricaded streets and set booby traps for police, setting up what they called an “autonomous zone”. In 2021, Portland was one of at least a dozen U.S. cities that had a record number of homicides. The same year, Antifa rioters tore through the city – causing $500,000 worth of damage – while police looked on helplessly because woke new laws stop them using pepper spray or tear gas. Homelessness is reported to have risen in the city by 50 percent since 2019, and drug-fueled scenes of shocking depravity have become commonplace. According to one article, “streets are overrun with tent cities and littered with trash. The issue is scaring away both locals and tourists”. In 2022, Portland’s record murder toll grew further.

According to the organization’s brochure, they also want to see the end of left-progressive policies such as Critical Race Theory in schools, taxpayer-funded abortion and transgender ideology infiltrating sports leagues. They argue that joining Idaho would mean lower tax rates and less red tape.

The rural/urban divide is, of course, far from a new phenomenon; its origins can be traced back to ancient Athenian political thought. However, the increasing sense of alienation and even hostility between major urban hubs and the provinces across the Western world over the past few decades can no longer be ignored and is likely to result in palpable political consequences elsewhere in the Western world too. This development comes hand in hand with how, from Canada through Germany to New Zealand, mainstream progressive politics have shifted to the Left on social issues since the fall of the Iron Curtain.

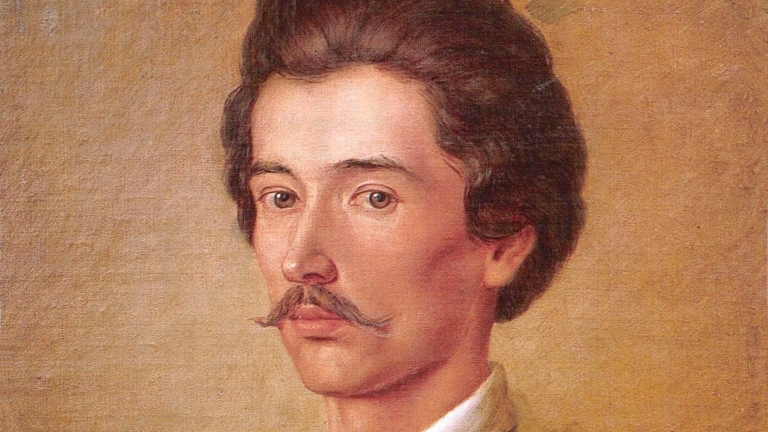

Take the example of the evolution of American politics over the past few decades. As Ira Stoll convincingly argues in his 2013 book JFK Conservative, the civil rights icon was squarely conservative by today’s standards. President Kennedy favored lower taxes and a strong U.S. military. He was firmly against using racial preferences and quotas to make up for historic racism and discrimination and opposed unrestricted abortion. He was a congenital anti-communist who, addressing the Massachusetts chapter of the American Federation of Labor in 1952, described Marxist ideology as “an enemy, power[ful], unrelenting and implacable who seeks to dominate the world by subversion and conspiracy”, asserting that “all problems are dwarfed by the necessity of the West to maintain against the Communists a balance of power”. And, despite of his string of extramarital affairs, the thirty-fifth President of the United States was a devout Roman Catholic.

Jumping three decades in time, even the policies pursued by Bill Clinton during his two-term presidency look conservative compared to modern terms. While on the campaign trail, Clinton came across as a tough-on-crime candidate (even backing capital punishment) who opposed legal recognition of same-sex marriage. In office, he went on to sign the Defense of Marriage Act, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, and extensive welfare reform. It is, in fact, highly unlikely that the former Arkansas governor would win the Democratic nomination today.

In his piece, Kotkin argues that there are now two prevailing realities in the States, with the Democrats increasingly depending on “largely single urbanites who embrace everything from radical transgenderism to critical race theory”. They are faced by a largely suburban or exurban, family-centric culture that is “more likely involved in basic industries like manufacturing, logistics, agriculture and energy”. He concludes that the battle between economically and demographically growing red states and Democratic heartlands “mired in lawlessness and decline” is no less than a clash of civilizations. And indeed, the upwardly mobile are flocking in ever greater numbers from California or New York to conservative-leaning states like Texas, Arizona, Florida and Tennessee that offer lower taxes, better job opportunities, family-friendly policies and public safety.

But unlike, for example, retirees relocating to the Florida sunbelt, campaigners seeking to secede from liberal Oregon have no intent on abandoning their ancestral lands. As the FAQ section on the movement’s website explains, “Our families pioneered these counties, so we don’t want to leave the land. We love our communities. We’ve invested years into relationships with friends, family, employers, churches, shops, and the land. It makes more sense for conservative counties to be under Idaho governance than Oregon governance. Eastern and southern Oregon voting patterns are very conservative; it would be expensive and wasteful for the majority of the 873,000 of us to try to find someone to buy all our homes and farms so that we can build new homes in Idaho”. To borrow from David Goodhart’s influential book, Greater Idaho supporters very much see the world from “Somewhere”. They are unapologetically rooted people who prioritize group attachment and security. And they are clearly not only tired of being governed from woke Portland but also prepared to take matters into their own hands.

Although Central Europe has, so far, largely been spared from the extremities of the American culture war, comparable patterns are emerging in the region. Poland has been described as being split down in the middle politically, with the voter base of the governing Christian-conservative PiS party heavily concentrated in the country’s eastern territories that were once held by Russia. Romania’s post-communist PSD party, which has ironically embraced social conservativism and maintains close ties with the Orthodox Church, is particularly strong outside what was once the Principality of Transylvania – said to be the final outpost of the West. And in Hungary, there has been much talk about the growing lack of political and cultural common ground between the country’s capital city and the countryside. The country’s 2022 election map shows that while the left-wing opposition did well in Budapest, almost all constituencies outside the capital backed the governing coalition led by Viktor Orbán.

There are occasional moments in Hungary when this tension surfaces. In an effort to prevent the possibility of fraud, an army of 20,000 opposition-affiliated vote counters descended on all corners of the country on election day in April 2022. Although no major irregularities were observed, their social media “reports” of the one full day spent at rural polling stations provoked heated debates about the increasingly wide rift between urban-dwelling intellectuals and the rest of the populace. One typical dispatch, from a town of 11,000 inhabitants an hour’s drive from Budapest, read: “a shockingly different world […] it was shocking to see how worn [their] hands were”. Another concluded that Fidesz-voting villagers “possibly would not have voted at all or for a different party had they known how much information is denied from them […] had they known gay couples raising children […] and how diverse people are”. Many, including the mathematician and public intellectual László Mérő, rightly pointed out that left-liberal urbanites are hopelessly detached from the reality experienced by millions of their compatriots.

So will we once see Budapest trying to break away from the rest of Hungary to form a progressive city-state or staunchly conservative eastern Poland severing ties with the country’s more Westernized part? Hardly. But the sharpening socio-political divide between cosmopolitan cities and more rural areas is here to stay, and steps must be taken across the aisle to connect and understand one another as members of the same nation. Otherwise, we risk our differences becoming unbridgeable.